Video Games: An Emerging Paradigm for Instruction through Neuroscience

Video Games as a Medium for Learning

Video games have become a cultural phenomenon-- games have fused themselves into our daily environments and become a ubiquitous part of life. It comes without surprise that interest in games as an educational opportunity has persistently grown alongside an interest in games themselves. As games began to break out from behind the screen and pervade reality, concerns have been raised from educators for games' level of violence and perceived lack of educational value. As more people begin to recognize the potential of games as a learning tool these concerns have diminished but still pervade traditional educational spheres. For educators who have long recognized the effects of digital culture and rising technologies, the emergence of video games as a medium for learning is unsurprising. Over the next few decades, society will likely witness a mass integration of multimodal and digital sources to supplement traditional educational practices and computational thinking methods, which will reshape the way we execute and view education.

Gamification, Game-based Learning, and Brain-based Learning

There is some confusion around these terms in the field of game education. Gamification aims to incentivize an activity that a person might otherwise choose not to do through the application of game elements, game-based learning balances educational goals like developing critical thinking with gameplay, and brain-based learning is simply the engagement of strategies based on body/mind/brain research.

Gamification has been as much of a topic of interest as it has been a topic of criticism for around a decade. Ian Bogost, who I’ve cited previously for developing the concept of procedural rhetoric, quite simply referred to gamification as “bullshit”. Now, he claims that he was not being “flip or glib or provocative”, but was speaking philosophically on the matter. Bogost recognized gamification bullshit as, more specifically, “marketing bullshit, invented by consultants as a means to capture the wild, coveted beast that is videogames and to domesticate it for use in the grey, hopeless wasteland of big business, where bullshit already reigns anyway.” (Bogost, I. 2011). Gamification isn’t all that different from Bogost’s concept of procedural rhetoric, which is “the art of persuasion through rule-based representations and interactions”; both gamification and procedural rhetoric elicit a response through game-based interaction. In theory, gamification has the potential for adding gameplay to non-gameplay realms in a successful, motivating, and entertaining way. But before that can happen, the approach to gamification must be applied in a transparent, ethical, and moral way-- that considers all the aspects of the game process (including the right rhetoric). Gamification in education is a developing approach that still needs systematically designed studies to confirm its educational benefits, as well as a critical approach for how to successfully gamify learning activities. (Dichev, C., Dicheva, D., 2017)

Game-based learning has long been employed as a means of education, but digital media, quite literally, is a game-changer. Video games as a digital learning tool have been gaining popularity and recognition from educators over the last two decades especially with games like Minecraft pervading classroom environments. For an “educational” game to be successful, multiple theoretical foundations-- cognitive, affective, motivational, and sociocultural-- must be considered and divergently emphasized based on the intention, design, and framework of the game (Plass et al., 2015, p. 258). The different learning styles, strengths, and senses of students should be critically examined. And, from a very simplistic perspective (although the process to make the core of a game “fun” is anything but simplistic), they must be fun, engaging, and compelling. The authenticity of an educational game derives from its ability to take learning material and give it vigor by transforming it into a game. Games that attempt to bombard students with curriculum and didactic methods will quickly lose player engagement. Most importantly, games should strive to inspire an interest in the subject matter so that students go beyond the game and are motivated to learn more elsewhere.

Neuroscience, psychology, and technology are all disciplines that brain-based learning (BBL) pulls research from. In educational, medical, and military spheres, video games can be used as a medium for BBL strategies to be employed. Brain-based learning employs knowledge from scientific research on the brain. This type of learning is not just limited to the classroom; BBL can also be extended to multiple mediums and industries. Brain processes can reveal the best teaching strategies, which when combined with games, may offer to be a valuable multidisciplinary learning tool. In this way, neuroscientists should not only be interested in the impacts and consequences of video games on cognition, brain function, and structure but also the neural factors involved in learning and how video games can be used as an educational medium and functionally designed.

The Brain of a Gamer

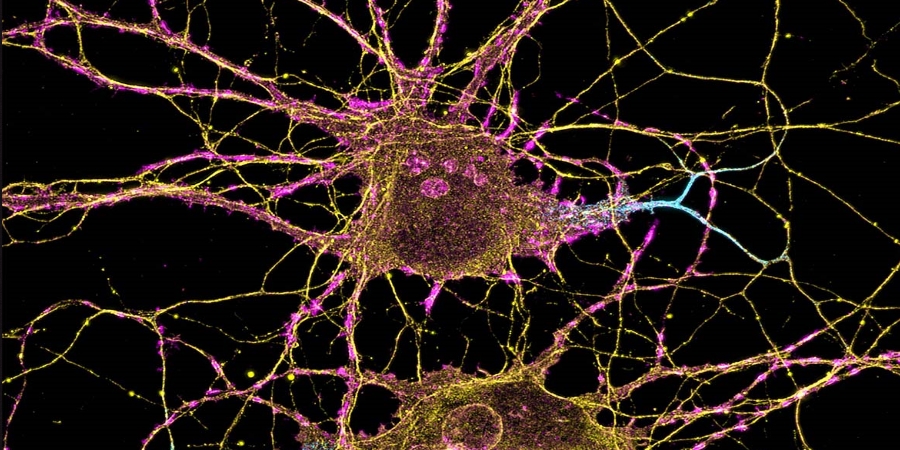

Discovering and experiencing a video game, like anything else, happens in people’s minds. When we learn, “our brain forms new connections and neurons and makes existing neural pathways stronger or weaker.” (Sterling, C. 2017). The malleability of the brain is also referred to as the brain’s “plasticity” which allows the capability of adapting to both our digital and physical environments. A gamer’s brain, particularly, will immediately recognize certain patterns and elements of a game from their previous interactions in games. A gamer might recognize patterns outside of game design in different contexts and environments, or approach a certain problem or task in the same way that they’d compete in or complete a challenge or quest in a video game. The role of a student, for example, plays the game of the curriculum. Students are constantly conditioned to ask themselves how they can achieve the grade they want. The grading system can either punish or reward and there are short and long term consequences compared to earning an A versus an F. Short-term consequences of poor grades might be getting held back a grade; similar to repeating a level or a loss of skill points in a video game. Long-term consequences of poor academic performance might be a greater difficulty in achieving upwards mobility or career progression, similar to the way a player may not be able to compete at a higher bracket in a competition. Depending on the time invested, students are likely to achieve a different grade, the same way players are conditioned in games to invest longer amounts of time to unlock certain rewards or abilities, or just generally improve their skill level and abilities. There are many areas of life that follow this linear punishment/reward system, but an individual with the “brain of a gamer” attributes, consciously or unconsciously, these patterns with certain aspects or elements of a game. In this way, a gamer might approach certain challenges or difficulties in life in the same way they would in a digital environment.

Dopamine Motivation, Feedback, and Reinforcement

The quality of learning will be affected by many factors, such as our attention, motivation, and emotion. When you’ve had some form of dopamine motivation, feedback, or reinforcement, the more likely you are to process and retain information. This applies not only to video game and academic contexts, but also to multiple areas of life.

In academia, identifying the features that make a game an effective learning tool is a key task in game-based learning. Games are designed with certain restrictions or limitations, sometimes through “representations and actions rather than spoken word, writing, images, or moving pictures.”. (Bogost, I. 2010) The acquisition of these rules are inaccessible to conscious recollection, rather, “acquisition and memory is demonstrated through task performance” (Koziol L.F., Budding D.E. 2012), which is a proponent of procedural learning, a form of learning that relies on tasks that require no attention. Procedural learning is thought to be mostly dependent on the basal ganglia (Willingham et al., 2002), which also mediates the effect of reward and punishment (Schultz, 2002). During procedural learning, “reward leads to enhancement of learning in human subjects, whereas punishment is associated only with improvement in motor performance.” (Wächter, T. et al. 2009)

Human attention is extremely limited; “when we are focused on a task, we fail to notice stimuli that are not related to the task.” (Hodent, C. 2019). This is a difficult challenge for game developers who are often trying to teach multiple rules and constraints of a game. A player engaged in a game is oftentimes required to challenge their full attention for a full sensory experience on a certain task at hand, which is an example of perceptual learning, an “...experience-dependent enhancement of our ability to make sense of what we see, hear, feel, taste or smell.” (Gold, J. I., & Watanabe, T. 2010). Perceptual learning is a very common learning process in game-based learning and across a number of game titles that challenge players to direct their full attention to specific tasks.

I would argue that game-based learning should heavily integrate procedural learning as a process that triggers the effect of reward and punishment, without demanding the full attention of players. Procedural rhetoric, a form of procedural learning, can be used as an art of persuasion for players to acquire and remember certain rules of a game. Procedural learning can be used as an opportunity for play and subconscious reward, stimulating motivation, feedback, and reinforcement. Meanwhile, perceptual learning can be used to teach specific tasks that require the full attention of the player. In this way, players can simultaneously learn about the certain rules and constraints of a topic while also receiving reward and positive reinforcement. Procedural skills and knowledge gained can be used when directing attention to a task of perceptual learning. Players will not be overwhelmed by information, and the information that is “lost” during phases of inattention will actually be supplementing the enhancement of learning and motor performance.

Citations

Bogost, I. (2011, August 8). Gamification is Bullshit. Bogost.Com. http://bogost.com/writing/blog/gamification_is_bullshit/

Dichev, C., Dicheva, D. Gamifying education: what is known, what is believed, and what remains uncertain: a critical review. Int J Educ Technol High Educ 14, 9 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1186/s41239-017-0042-5

Plass, J. L., Homer, B. D., & Kinzer, C. K. (2015). Foundations of Game-Based Learning. Educational Psychologist, 50(4), 258–283. https://doi.org/10.1080/00461520.2015.1122533

Sterling, C. (2017, July 25). What Happens to Your Brain When You Learn a New Skill? CCSU Continuing Education. https://ccsuconed.wordpress.com/2017/07/25/what-happens-to-your-brain-when-you-learn-a-new-skill/#:%7E:text=Each%20and%20every%20time%20we,%E2%80%9Cplasticity%E2%80%9D%20in%20the%20brain.

Hodent, C. (2019, July 23). Understanding the Success of Fortnite: A UX & Psychology Perspective. Gamasutra. https://www.gamasutra.com/blogs/CeliaHodent/20190723/347166/Understanding_the_Success_of_Fortnite_A_UX__Psychology_Perspective.php

Gold, J. I., & Watanabe, T. (2010). Perceptual learning. Current biology : CB, 20(2), R46–R48. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2009.10.066

Koziol L.F., Budding D.E. (2012) Procedural Learning. In: Seel N.M. (eds) Encyclopedia of the Sciences of Learning. Springer, Boston, MA. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4419-1428-6_670

Wächter, T., Lungu, O. V., Liu, T., Willingham, D. T., & Ashe, J. (2009). Differential effect of reward and punishment on procedural learning. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience, 29(2), 436–443. https://doi.org/10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4132-08.2009

Bogost, I. (2010). Persuasive Games: The Expressive Power of Videogames (The MIT Press). The MIT Press.